I used to bask like a cat on a sunny window sill in Mom’s bright yellow kitchen, a daisy-wallpapered haven from the moody Iowa weather and our creaking wood-frame house, haunted somehow, remnants of bad nights and sad scenes hanging like cobwebs in the corners. In the other world of the yellow kitchen, Mom’s secret for chocolate chip cookies was extra vanilla extract; then take them out while they’re still a little gooey. When you make a birthday cake, line your pans with margarine and waxed paper. Lay yesterday’s newspapers over the drop-leaf table to catch the drips when you’re dyeing Easter eggs. That February night, we were making dinner. I was helping Mom wash a chicken and get it ready for the oven. Together, we dredged the pieces in floury coating and lay them in a shallow pan, a little canola oil, twenty-five minutes a side. As the skin gets brown and crispy, the cold house fills with the smell of food cooking, a robust, restorative smell for the living, that holds the ghosts at bay.

While Mom worked on the vegetables, I stirred hot milk and melted margarine into mashed potato flakes, chattering all the time about Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, my current library book. That reminded her. “I found something for you, Jennie,” she said, indicating a Xeroxed flyer I hadn’t noticed lying on the table. I put my big spoon down and went over to sit in a ladder-back chair under the wicker-shaded hanging light. Dates and times for something, a weekend activity, Friday after school, all day Saturday. Bookbinding. For kids? I didn’t know. Could I give up a whole Saturday? I’ll be finishing Charlie and the Chocolate Factory soon. After that, there was the stack of Nancy Drews I’d gotten for Christmas. I couldn’t get enough of Nancy and her friends, that trio of girl sleuths. I’d been going to start The Secret in the Old Lace. When I looked up from the flyer, Mom was beaming, waiting to hear what I thought. Wasn’t this a great idea?

I wanted to make her happy but, no. Bind a book? What book? And where? Some drafty back room at the library? Mom meant well but she didn’t know how much I needed to escape on the weekends. I’d tried to tell her and she had tried to understand, but how could I explain? Why was I so overwhelmed, so clumsy, so awkward with the kids at school? If I was nice to them, they’d be nice to me, Mom always said. It was so easy. But somehow, I couldn’t be nice when other kids weren’t. I should be more cheerful, Mom would say. Nobody likes a long face. That was true. But my books didn’t care what shape my face was. And I could get lost in them, pleasurably lost, in a log cabin hidden in the Big Woods, in a house called Green Gables, sailing over the Atlantic on a giant peach. I loved reading books, not binding them. So did I want to do this class? Well. “Do I have to?”

Her smile dimmed. “Don’t you want to? I thought you’d be excited.”

“Really?”

“Don’t you want to write a book?” What? Write a book? Is that what it said? I looked again at the plain white page in my hands. Mom was speaking as she crossed the kitchen, but what was she saying? Some strange hum drowned out her words. I saw her finger pointing to lines I hadn’t noticed. Write your own story. Draw your own illustrations. My teachers had always praised my writing assignments, had gushed over them, even, but could I write a book? I’d read so many, had soaked them up, savored them. But were any of my own stories worth telling? “And look. You write the story, make the pages, then you bind them together.” Bookbinding. Of course. And of course, I should do it. Look at her face, wanting something good for me, eyes full of hope. But what about the other kids? Other kids always ruined everything with their cliques and their judging. Maybe Mom read my mind. “You can do this,” she said.

But there were fees and Dad wouldn’t see the point of this, wishing instead that I were sporty. Why not softball, he always asked. Or basketball, if it was winter. Why spend money on violin lessons or art classes? A writing workshop? That was leading nowhere.

Mom said she’d figure out the fees. She’d talk to Dad. But who would take me to a writing class on Friday night? Mom would be at the office until five when she rushed home, started dinner, ran laundry, served the meal, washed dishes, and finally, wearily, badgered Dad to take out the trash. Dad taught school, left work at 3pm, and spent his afternoons at the bar, but drive me across town for an optional extracurricular? No way he was available for that. Just as I realized how much it would mean to join the class, it was impossible after all. What if I stomped down the stairs to the basement TV room right now, stood between my dad and the screen, hands on my hips, and called him a bad father, a mean man, a selfish tyrant? “Don’t worry,” said Mom. She’d leave work early and drive me herself. How could she? She’d find a way. I should have been happy. Instead, I hid my angry face and made myself act calm, but I wasn’t.

A few weeks later, I walked home from school on a drizzly Friday afternoon, past the brick and stone houses belonging to families richer than mine, kicking water, and twirling my plastic umbrella. I wished I had a yellow rain slicker with a matching hat and rubber boots like the ones kids in cartoons wore on rainy days. I’d be as cute as a toy duck, puddle-jumping, and laughing with my rosy red cheeks. When I got home, I used my key to unlock the empty house, its rooms as dark and gloomy as the weather, a blanket of silence smothering any echo.

Upstairs, raindrops tapped on the wavy glass of my century-old bedroom windows, rattling loose in their frames with every gust of wind. No one would be home for hours so I climbed into bed with a book to pass the time, stuffed toys and soft pillows to lean on, quilted comforter wrapped like a royal robe around my shoulders. I was a princess in a tower, the queen of the castle, an orphan girl rescued from an uncaring world. The bedside lamp brightened the gray afternoon, casting a yellow light over the clock radio and ceramic white cats on the nightstand. Beside them was the box of tissues I kept for the sad parts, when the dog died, the bad news came, and nothing would ever be the same again.

I read with no notion of time outside the book. If doors opened and closed downstairs, if someone called my name, I didn’t hear. I was in Wonka’s chocolate factory where the wallpaper was fruit flavored, where squirrels separated good nuts from bad ones, and a fizzy drink could fill your belly with gas until you floated right up to the ceiling. The library check-out card had my name written on it four times. The library was full of doors to other worlds, other ways of living, city kids who grew up in apartments and rode the subway, smart kids who ran detective agencies, lonely rich kids whose rich parents ignored them. When I asked the librarian for a better book about a dog than Old Yeller, she gave me Where the Red Fern Grows. After The Secret Garden and The Little Princess, she suggested The Island of the Blue Dolphins and Jacob Have I Loved. When I finished Hatchet, she made sure I didn’t miss Julie of the Wolves.

My bedroom door flew open and banged against the wall. We were late. Late for what? “Your writing workshop,” Mom said, drawing back the blankets and grabbing my hand. In the bathroom, she dragged a brush through my hair. Downstairs, she put my coat on me and pushed me out the door.

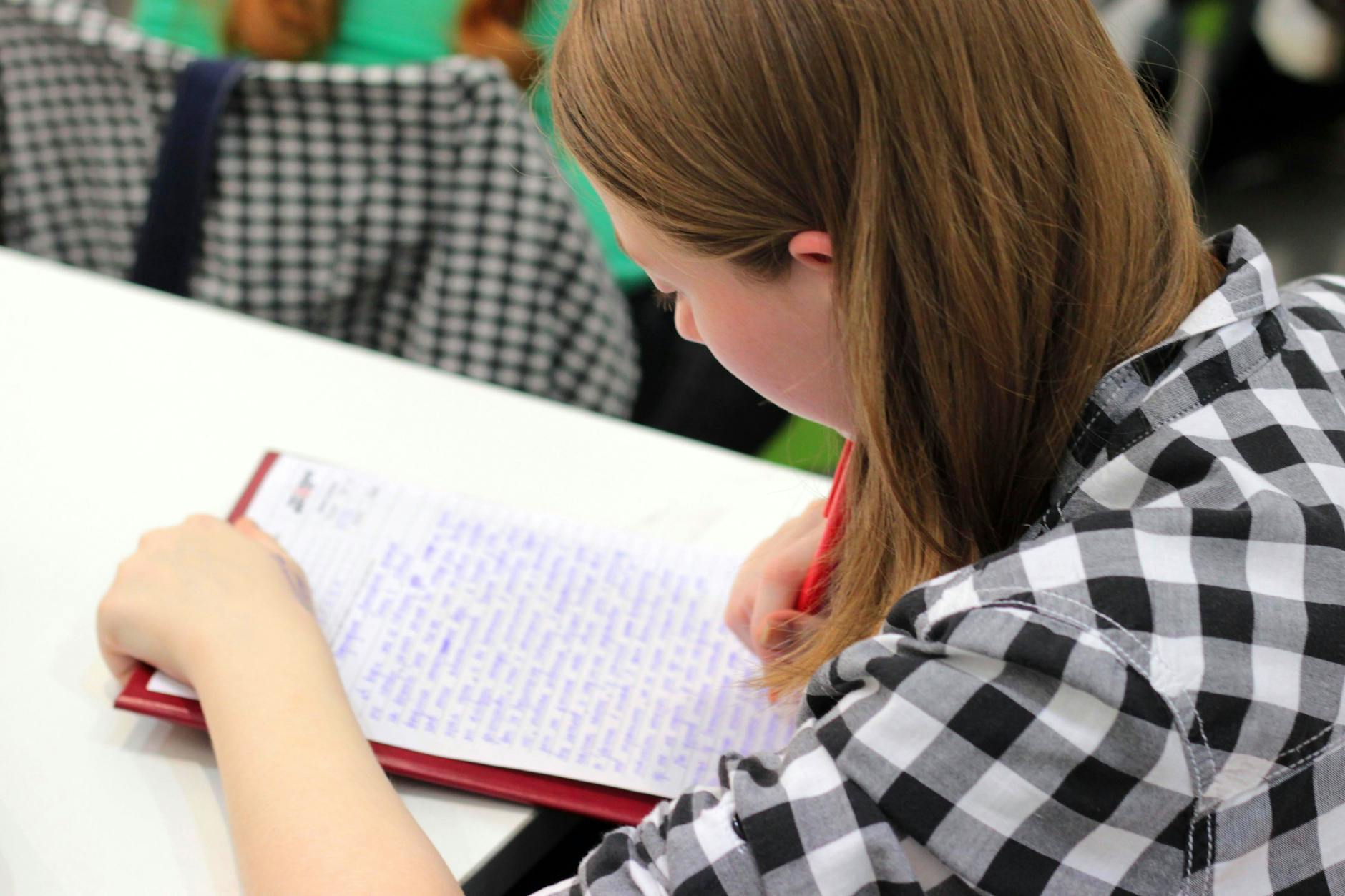

When we got there, we hustled across the dark, wet parking lot and through the big glass doors of the community center. An acre of grey carpet stretched across the lobby under fluorescent lights as a lady wearing a sweater vest beckoned us to the meeting room. Behind her, the view through another set of doors showed a man up front writing on a whiteboard while a roomful of kids, aged eight to eleven, sat in rows at long tables. Mom kissed me at the door as I struggled out of my coat. I settled into the empty back row where I took a seat next to a stack of lined paper and a tray of pencils while the man up front, ignoring the distraction, continued explaining basic paragraph structure. “Main idea. Three supporting sentences. Conclusion.” Was that all? I’d learned that in first grade. Were these other kids stupid? I hoped there would be more to the class than this.

The man was a high school English teacher, younger than most, and in spite of the pedestrian start to the lesson, his enthusiasm hooked me. He filled the whiteboard with hasty diagrams: fiction versus nonfiction, a simple story arc, a scrawled list of familiar genres. “For this project, we’ll write fiction. But will your story be a comedy or a tragedy? A fairytale or a mystery?”

We took a break at 6pm, very grown up, but I was the last to leave my seat, hanging back from the group in the gray-carpeted lobby, trying to observe the other kids without catching anyone’s eye. Still, a girl in stonewashed Guess jeans and a pastel pink sweater walked up and introduced herself. What was my name, she asked, and which school did I go to? Over her shoulder, I could see a few of her friends watching from across the lobby, one girl with her hand cupped over the ear of another, two others standing side by side with their heads together.

“Jennie McArthur. Grant Wood Elementary,” I said.

“I go to Pierce.”

Pierce. Her family was probably richer than mine. Designer jeans, cool sweater, tinted lip gloss. And friends. So why was she over here talking to me? Be nice to them and they’ll be nice to you. But girls like this never were. Whatever I told her would be good gossip to take back to the giggling girls, big laughs with the other kids about me, the weirdo in cheap clothes who wouldn’t talk to anyone. We could never be friends.

“You like writing?” she asked.

“Yeah. Well, excuse me.” I escaped to the bathroom and stayed there until the break ended. I thought about Guess Jeans Girl and the other kids I’d seen, sizing them up in my mind. Were any of them good writers? Were they better than me?

Back in our seats, we filled in story outlines with our chosen genres, characters’ names, and our stories’ main conflict. From my place at the back, I could tell that Guess Jeans Girl didn’t know what to write. She sat there between two girls just like her, one in a fashionable mint green sweater, the other in powder blue. The three of them elbowed each other and whispered, scribbling, then erasing. Dumb-dumbs. When I finished my worksheet, I began drawing in the margins, adding curlicues to the typeface, and extending the answer lines into flowering vines. At 6:30, it was finally time to write, following our outlines to draft our stories, and getting as far as we could before the session ended in half an hour. Half an hour? It wasn’t enough. Not nearly enough. The night was practically over just as we got to the good part.

At 7pm, the others filed out through the swinging glass doors giving me quizzical looks which I ignored as I continued to write, my usually impeccable handwriting now almost illegible as I rushed to keep going. The boys were the first ones out, followed by the Trendy Sweater Brigade and the rest. When everyone was gone and it was time to turn out the lights, the lady in the sweater vest approached me. I kept my head down. “Five more minutes,” I said.

“I’m afraid not. You’ll have more time in the morning.” I had an impulse to growl at her and argue, but her face was too kind. Behind her, Mom smiled and waved through the glass doors. I suddenly had so much to tell her. The lady in the sweater vest looked relieved when I put my pencil down and grabbed my coat.

“See you tomorrow,” she said.

“See you tomorrow.”

We walked out, Mom holding my hand as we crossed the parking lot, and on the drive home, I told her everything. Nobody else got what the teacher was saying. I was the first to finish my outline and the last still writing when the clock ran out. I was the only one taking this seriously, the only one with enough talent to write a good book. Guess Jeans Girl and her friends would all write the same story because they only had one idea among them. Why were they even here? Mom stopped me. “Pride is a sin.”

“It isn’t pride, it’s the truth. Why can’t I say I’m the best when I am?”

“You don’t know that you are,” she said. “You didn’t see what the other kids wrote.”

“I saw how they didn’t know what to do, how they wasted time, and copied each other’s answers.”

“It’s wrong to spy on people. Keep your eyes on your own work.”

“I don’t spy. I just see what I see.”

“You won’t make friends by looking down on people.”

“They look down on me.”

“No, they don’t, Jennie. That’s in your head.”

“It’s not in my head.”

“Stop arguing. Just stop it.”

If I’d been with Dad, I’d have fought him just for the sake of it, raised my voice to make him mad, refused to back down when he raised his, too thick-headed and stubborn to ever give in. But for Mom, I piped down, though inside, I thought I was right, that she didn’t understand, and never would. I apologized for arguing and she accepted, saying, “You probably are the best in this class, Jennie. But the other kids aren’t stupid. Maybe you know it all tonight, but you’ve got plenty to learn.”

The Saturday session was crammed with brainstorming activities, revisions, and final drafts. The hours passed, as Guess Jeans Girl and her pals struggled to finish their stories, the English teacher leaning over their shoulders to explain his corrections. What was he saying? I imagined him telling them that they just weren’t cut out for this, they’d never be writers, they may as well quit now. That’s what I’d have told them. Most of the others were doing much better, recopying their stories in their best handwriting, and taking them to the little side room where a school secretary had volunteered to type them up. I’d been among the first to finish and now I worked on my cover and title pages.

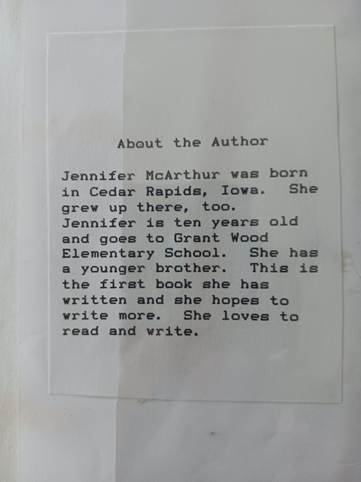

I called my book The Mystery at 2316 Langley Boulevard. A pretty, popular young girl named Nicole, with the help of two faithful friends, solves a mystery, and nabs the thief who made off with her mother’s heirloom ring. It owed much to those Nancy Drew novels I loved with overtones of Encyclopedia Brown and a hint of Nate the Great. At ten pages, front and back, it needed a lot of illustrations, pushing me to work as fast as I could. Drawings for the second half of the book were less than my best and the final courtroom scene was rushed, practically unfinished. But I was done in time for the last step: bookbinding. Kids who were ready (none of the girls in sweaters) glued their finished pages onto heavy sheets of paper which were folded to form a book, then sewn along the spine with darning a needle and white string. With the addition of a little cardboard and a clear plastic cover, I’d made a book.

I rushed into Mom’s arms when she came for the parents’ hour at the end of the day. Dad had stayed home, drinking beer and watching sports on TV, I guessed. I showed Mom around my work area, showed her my pens, pencils, and the mismatched markers I’d used for the drawings. With the other kids and their parents buzzing around in the background, I sat her down and read my book aloud, leaving long pauses so she could soak in the pictures. When I asked if she wanted to read it again, she did! I floated on a cloud beside her, rereading my words over her shoulder. The English teacher came up and told Mom what a good student I’d been. The lady in the sweater vest said I was more diligent than the rest, I’d kept working when the others broke for lunch. The secretary paused on her way out with the last of the typed manuscripts. Was I Jennifer McArthur? My pages had been the easiest to transcribe, she said, because of my beautiful penmanship.

I was buoyant all the way home, my book in my hands, turning the pages over and over. From the driver’s seat Mom was telling me how proud she was, how she’d known all along that I would make an amazing book. But what would Dad think, I wondered as Mom kept talking. He’d be impressed, I decided. He would have to be; everyone else was, and he’d have to admit that this time, I’d finally done something worthwhile. Look at the pictures I’d poured so much effort into, the professionally typed pages, and the neatly stitched binding. He’d see that this was just as much to be proud of as playing shortstop on the girls’ softball team, that this was the real me, right here in my hands, and I was offering it to him. He would praise my work, yes, he would, and he would love me so much.

When we got home, I hurried downstairs with Mom close behind me. “Turn the TV off, Mac,” she said. Of course, he didn’t, but he lowered the volume, listening as I read aloud, glancing up from his crossword to give the illustrations a onceover. “I guess it wasn’t an art class,” he said with a smirk, referring to the flaws in scale and irregularities between pages. I’d hoped he would see beyond the mistakes, but at least his criticism was mild. Mom told him to keep his negative thoughts to himself. I’d been short of time for the drawings, I explained, but did he like the story? Yes, he liked it, liked that I’d used a vocabulary word like “heirloom.” My grandmother, the retired English teacher, would be impressed with that. Yes. You see. He loves me and he is proud of me. “Nice work, Kid,” Dad said to me, ruffling my hair. He knew I hated it, always did it just to get a rise out of me, but tonight, I wouldn’t start a fight.

Girl, Writer is an excerpt from the memoir-in-progress, An Unhappy Happy Childhood. An earlier version appeared on LALCS MSMU, January 2024. Find it at Latinx Memoir Fall 2023 – On The Edge.